First, some background. Matt broached the subject a little while ago in response to the youth vs. experience narrative being peddled during the cup finals. To summarize:

Experience is valuable insofar as most NHL players get better at their jobs over their first few seasons, but past that, its value is equal parts marginal and mythical...

The mythical part is rather straightforward. Tomas Holmstrom has been through the wars, but you can count on Sidney Crosby to make better decisions with the puck and create more scoring chances, because he's Sidney Crosby -- he's a better hockey player. Holmstrom's experience probably makes him a bit better player than a 21-year-old with his same size and skill set, but it doesn't make him a better player than Sidney Crosby.

Meaning experience is a pertinent contributor to success inasmuch as it effects the progression and development of a given player. To be explicit: hockey players have a virtual "floor" and "ceiling" in terms of their abilities and output. The range/levels of their floor/ceiling is mainly determined by skill, ie; how good a hockey player they are. Crosby's floor, for example, is well above Wayne Primeau's ceiling, meaning a team of 21 year-old Crosbys is likely to beat up on a team of 27 year-old Primeaus every single time, despite the fact the Primreau club would have the experiential edge.

Of course, a player's abilities (relative to himself) tend to expand as they physically mature and gain at-bats. It's generally accepted wisdom that most players usually reach their ceiling - or peak - around the age of 27/28 (usually after 5 seasons worth of play). The best tend to plateau for awhile, others drop off due to injury, fatigue, wear-and-tear. If Im not misrepresenting him, Matt's point is two-fold:

1.) A players skill, rather than his experience, is the more consequential factor when it comes to performance and success. While a 27 year-old Crosby is superior to a 21 year-old Crosby, the younger version is still probably superior to most other players in the league - experienced or otherwise.

2.) Experience, as it's framed and conceptualized in the MSM's typical narrative, is mythical since it's gains don't actually tend to be additive or useful after a player reaches his peak. For example, play-off games number 100 and 101 probably weren't any more instructive or useful to Chris Chelios than games number 80 and 81. At a certain point, like painting a window black to block out the sun, progressive "layers" of experience become less and less relevant.

Tom's reponse:

Hockey is a game of mistakes. David Staples has started counting errors leading to goals as a new statistic. The number isn't particularly valid, but the salient point is that it is not hard for him - or anyone else - to find mistakes on every scoring play or scoring chance.

As players gain experience, they eliminate mistakes. This - more than anything else - is how players improve. They learn what they can and cannot do at the NHL level. They learn when they can force the play and when patience and the safe play is right. They learn when they can pinch and when they cannot. They are less likely to take stupid penalties.

Even experienced players make mistakes and a creative player like Crosby or Malkin can actually force errors. Therefore there is no such thing as a perfect game. But experienced teams recover quickly and minimize the impact of the inevitable gaffes. Inexperienced teams tend to compound errors.

Tom's point is, I think, technically less principled and more pragmatic on the team-building front: a club with too many kids and rookies is more apt to be error-prone, as a larger portion of the team will be closer to it's "floor" than it's "ceiling". So while skill may be a a greater contributing factor - as in the Crosby vs. Primeau example - the issue is: there is a distribution of skill across players on a team (and the league in general) and the Crosbys and Malkins of the world are outliers, or, exceedingly rare. Therefore, a team with a lot of inexperienced players - players near the onset of their careers - is likely to be worse than the experienced squad since, all things being equal, the average NHLer at 27 is better than the average NHLer at 21.

Anyways, I promised in Tom's comment thread to put together some of the data to see what could be found. Here's what I cobbled together so far:

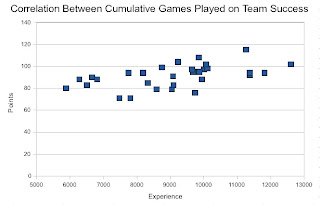

Experience (regular season games played) and points (07-08) by Team

Graphed

Method:

basically, I went through and summed the cumulative games played (regular season) of every player for each team's roster as a metric for experience. I considered using "age", but that seems like a pale proxy for experience as opposed to actually playing games.

I smoothed the data-set out a bit by excluding goaltenders and paring each roster down to just 23 skaters (roster sizes were variable, depending on trades, call-ups, injuries, etc.). The "23" figure was fairly arbitrary, though it seemed to capture all of the significant contributors while excluding cup-o-coffee guys. Probably anything from 18-22 would have worked as well.

Even though I posited earlier that experience becomes less relevant past a certain threshold, I decided to use cumulative games played as the independent variable because I initially wanted to investigate the prevailing (or "mythical") conception of experience and it's contribution to success. Perhaps, for example, there are benefits to being "veteran" beyond landing on the meaty portion of a player's career arc: dressing room presence, "leadership", respect for and from teammates, etc.

Not that this investigation speaks to that in any meaningful way. As you can see, the data yielded a positive correlation between "total games played" and "regular season points" for the prior year of 0.53. Not perfect, but hardly inconsequential. Unfortunately, as it's set-up now, the analysis probably conflates a lot of the factors we're trying to separate out and doesn't necessarily elucidate any causal relationships. This is more a beginning of the discussion than the conclusion I guess.

A more thorough investigation (by someone more math savvy) would be in order. I have the raw data, which can be be further parsed and correlated by anyone else interested. I may or may not do my own follow-up on the subject...

-----------------------------------------------------------------

There's a famous SNL skit about the Blue Oyster Cult's "Don't Fear the Reaper", featuring Christopher Walken and Will Ferrell. In it, Walken plays producer Bruce Dickinson who "has a fever for the cowbell". No doubt a fair measure of the skit's comedic value comes from the juxtaposition between Ferrel's typical obnoxious flailing and Walken's now iconic flat stare and wooden delivery. However, the underlying joke the skit is predicated upon is Dickinson's (Walken's) manic and nonsensical obsession with the cowbell, which is a relatively inconsequential aspect of the track.

In a way, I think a lot of fans and even coaches or GM's have their own "cowbells": those factors they foreground and elevate above and beyond their true values. Personally, when I played hockey myself, I was under-sized and I survived via speed and agility. Now, the smaller, quicker players are the ones that elicit my sympathies (which likely explains my continued quest to insulate Lombardi from criticism). One of the reasons the above inquiry was interesting to me is I consider "experience" to be one of Darryl Sutter's cowbells: he seems to have a fever for it, even though it's contributions to the tune may be minimal.

Of interest to Flames fans is the fact that Calgary was one of the most experienced clubs in the league last year, in terms of total career games played, but had only middling results. Most notably, Calgary had the fewest number of roster players with less than 410 games played (the equivalent of 5 full seasons of hockey), at 9. An unofficial per-team average for "inexperienced" players (less than 410 games) was about 12 or 13. A lot of teams with a greater number of inexperienced players did better than Calgary last year (though, a lot of teams with inexperienced players also did worse).

I see Sutter's experience fetish as a cowbell* because it seems to override the contribution of skill - the "floor/ceiling" factor - in a lot of cases. As previously discussed, guys like Eriksson, Primeau, Friesen etc. were given higher salaries and preference over younger potential replacement level players despite the fact they wouldn't be getting any better and were pricier. Beyond creating a hostile development environment (as previously discussed), the other problem in light of this discussion is Eriksson et al. sucked, experience or no. Their ceilings were low. The totality of events, that treasure trove of games played, didn't amount to much because, well - they just weren't very good players.

I think - and further explication of this issue may or may not prove this accurate - that Sutter can pound on that cowbell all he wants, but it wont make the track any better without taking into account other, salient factors (like skill-level, cap efficiency, etc).

*(Other Sutter cowbells include: Western Canadian guys, former first round draft picks and former "Sutter" players).